It is an undeniable fact that the number of amputations performed in this and other countries has been greatly augmented of late years, attributable no doubt to the numerous accidents occasioned by the increasing use of Machinery and Steam power in all departments. This circumstance, in conjunction with the casualties of the late war, have caused the subject to be prominently before the notice of the medical profession.

William Robert Grossmith, Amputations and Artificial Limbs, (1857)

Trade Card for Sleath’s Improvements, 18th C (c)Fitzwilliam Museum

Trade Card for Sleath’s Improvements, 18th C (c)Fitzwilliam Museum

Advertising Feature for Sleath & Jackson, c1800 (c)British Museum

Advertising Feature for Sleath & Jackson, c1800 (c)British Museum

When Emma Sleath married James William Skelton on 21st Nov 1866 at St Giles Church, Camberwell, at the age of thirty, she may well have been relieved to be finally leaving her family to marry such an eligible bachelor. A successful West India merchant who had grown rich through trading in mahogany (see A Tale of Exploitation), James William was a respectable decade older than Emma, as well as having a substantial home on the outskirts of London – Westle House in Moreland Road, Croydon. Whether Emma knew about his British Honduran daughter, whom he’d fathered while establishing his business out in the Caribbean, is open to question. However, with three decades already behind her, Emma would not have been naïve in the ways of the world, and had possibly already resigned herself to the fact that marrying an older successful man necessitated taking on some sort of baggage.

Of course she may even have been delighted at the thought of becoming a step-mother, and had perhaps already established a good relationship with the teenage Louisa Arabella. Yet what can often be an emotionally fraught situation today, would no doubt have created the same conflicts for the Victorians – particularly when it came to the issue of illegitimacy. But having witnessed her father’s early death and her mother’s fast re-marriage, followed by the birth of two half-siblings, Emma would possibly have accepted this situation as an inescapable part of life in the mid-nineteenth century (where death was always lurking close by).

Emma’s Father, John Henry Sleath, had died suddenly of apoplexy (a cerebral haemorrhage) in early 1843 at the age of forty-five, when Emma was just six. Only several months after this tragic event, her mother quickly, and perhaps rather sensibly, went on to marry her late husband’s younger business partner, William Robert Grossmith. The Sleath family had established their successful business in Fleet Street a century earlier, when they had grown wealthy through supplying trusses and artificial body parts to the Georgian Court and high-ranking military. What the Sleaths (and their business partners) had learned to excel at over the years was the mechanics of creating life-like and moveable prosthetic limbs, an invention which Emma’s stepfather would continue to develop further.

In fact, so well-respected was William Grossmith that in 1856 he published a book on the subject: Amputations and Artificial Limbs (or Grossmith on Amputations, Artificial Legs, Hands &c.) Surprisingly, this was not the first book to which his name was attached – in 1827, shortly before his ninth birthday, the ‘memoir’ of his life as a prodigy child actor was published. Entitled The Life and Theatrical Excursions of William Robert Grossmith the Juvenile Actor, not yet nine years of age, this book followed on from a shorter pamphlet, published in 1825, with the title The Life of the Celebrated Infant Roscius, Master Grossmith of Reading, Berks, only seven years and a quarter old.

Although William Robert Grossmith is a very tenuous connection to the Skelton family (not only was he Emma Sleath’s step-father, but Emma herself is not a blood relative), he is, nevertheless, an important one in the history of the Sleath-Skeltons. His early success on the stage and his theatrical connections can be claimed to be one of the influences on Emma’s youngest son, the Edwardian actor-producer, Herbert Sleath-Skelton – who went by the stage name of Herbert Sleath. (More about this colourful character here).

William Robert Grossmith was a relatively famous child actor in the 1820s, and deemed to be ‘the Infant Roscius’ of his time. His younger brother, Benjamin Grossmith, also went on to follow him on the stage at a very early age. This was towards the tail end of the hey-day of the Georgian child prodigy actor (which also included girls), the most famous being Master Betty, or William Henry West Betty, said to be the original ‘infant Roscius’ – Roscius being a term once used to describe an actor of outstanding talent (after the famous Roman actor, Quintus Roscius), but which may be unfamiliar to readers today.

William Grossmith in various acting roles c1825 (c)British Museum

William Grossmith in various acting roles c1825 (c)British Museum

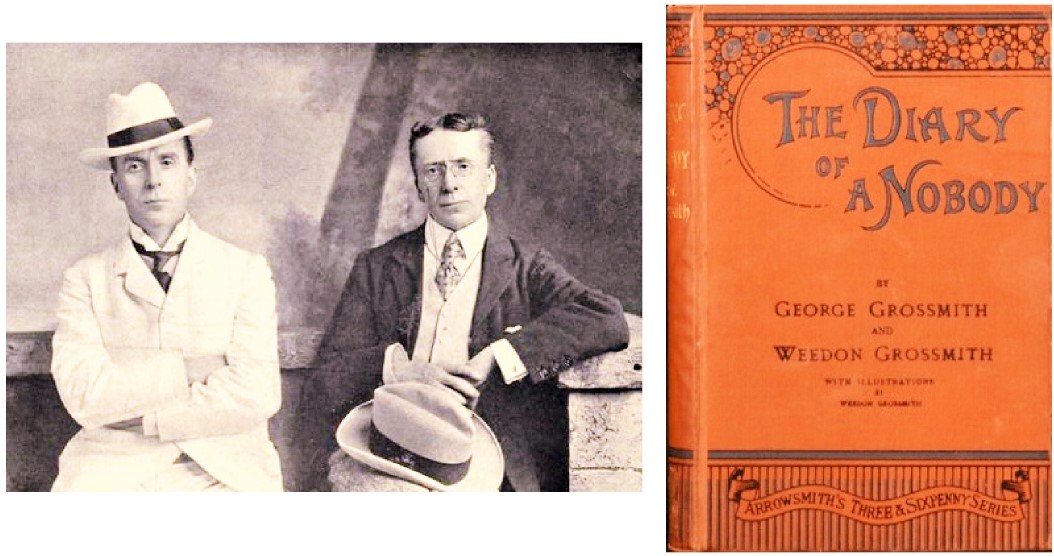

And if this was not enough to excite a humble family historian such as myself, I discovered that William and Benjamin Grossmith had an even younger brother who also had a gift for impersonation – George Grossmith I. Not only would he become the father of George Grossmith II (who had a famous son, George Grossmith III, hence the numbers) and his younger brother Weedon, but he was said to be a talented and humorous solo performer in his own right. His sons later said that their father would leave his family in London for several months of the year in order to tour the country with his entertaining literary ‘lectures’, a task he was somehow able to combine with his day job as criminal court reporter for The Times (a role which George II eventually took over). His famous sons, George and Weedon Grossmith, went on to become successful and multi-talented actors, producers, writers and artists, and are perhaps best remembered today for their illustrated (and very funny) book The Diary of a Nobody, first published in 1892.

As you might imagine, the discovery of this connection to the famous Grossmith Family left me elated. As a teenager I had watched the 1979 BBC adaption of ‘The Diary’, although it was my younger sister who owned a copy of the book (being more interested in social history at that time), and who was particularly taken with the story of the trials and tribulations of the deludedly aspirational Pooter family of Holloway. However, the Grossmith brothers had themselves grown up in a very different household to the fictional characters they lampooned. Theirs was a very middle-class and Bohemian upbringing, where famous actors of the day, including Ellen Terry and Henry Irving, were regular guests to the family home, alongside prominent literary figures, such as George Sala.

George Grossmith I

George Grossmith I

Weedon Grossmith and George Grossmith II (and ‘The Diary‘)

Weedon Grossmith and George Grossmith II (and ‘The Diary‘)

What was perhaps even more surprising to discover was that Evelyn Waugh’s father, Arthur – who professed ‘The Diary’ to be one of his favourite books – would often read out extracts to his sons during the frequent evening theatrical reading sessions in his study. Those readers who have followed my genealogical quest from its beginning (see Begin Again) will know that it was the documentary, Fathers and Sons, (and Alexander Waugh’s accompanying book) about the male line of the literary Waugh family that first re-ignited my interest in returning to research my own family history. So it was with a certain sense of satisfaction that I learnt of this coincidence.

Indeed, in 1930 Evelyn Waugh went so far as to make the following observations on the Grossmiths’ book in the Daily Mail newspaper: I still think that the funniest book in the world is Grossmith’s (sic) Diary of A Nobody. If only people would really keep journals like that. Nobody wants to read other people’s reflections on life and religion and politics, but the routine of their day, properly recorded, is always interesting, and will become more so as conditions change with the years.

The Australian academic, Peter Morton, suggests that Waugh not only identified with the Pooters’ wayward but ‘modern’ socially climbing son, Lupin, but could see in Mr and Mrs Pooter the petit bourgeois sensibilities of his own parents (from which, just like Lupin, he wished to escape). It would appear that in later life Waugh made an extensive study of the diary, comparing it with the original series published in the magazine Punch from 1888 to 1889. This was after receiving a copy from his mother at Christmas in 1946 – something that may have been prompted by his mention of the diary in his recently published novel, Brideshead Revisited (where Lady Marchmain reads extracts to her family).

But our story of the Grossmiths, like Alexander Waugh’s investigation into his family, begins with an earlier generation: namely with the prodigious talents of Emma’s stepfather, William Robert Grossmith (uncle to the more famous Grossmiths who succeeded him). Born in Reading in 1816 (although said to be born in 1818!), William was the oldest son of a Looking-Glass and Picture Frame Manufacturer (that very title conjuring up the Victorian mysticism of Alice and her adventures).

Even as an infant, William seemingly already showed great talent for memory and impersonation, and a visit to the local theatre at age six appeared to have left an impression on him. Thereafter he began to learn theatrical songs off by heart, showing an aptitude for singing tunes by ear. When his father introduced him to Charles Kemble, an actor and the manager of Convent Garden Theatre, Kemble described the young Grossmith as the greatest theatrical prodigy he had ever met with and advised the elder Grossmith to first try him on the boards of one of the minor theatres.

After success in 1824 at the Royal Cobourg/Coburg Theatre in Southwark (now The Old Vic) performing several popular comic songs of the age – an opportunity which came about due to an introduction to James Jones*, the theatre’s founder – young William withdrew from the stage at the behest of his mother, who was concerned about the effect acting might have on his moral development. However, shortly afterwards this bright and inquisitive child encountered the works of Shakespeare, and began to learn to recite whole plays, all the while displaying a full range of adult emotions. His particular favourite was Richard III, and so it came to pass that several months after ‘retiring’, the Infant Roscius was back at The Cobourg, acting out scenes from this play to a rapturous audience, as well as playing to the Sadler’s Wells Theatre for one week (after being offered a more lucrative contract by the Manager).

* The first book to describe William’s juvenile career (in 1825) was dedicated to James Jones who has since honoured him with the title of his ADOPTED CHILD.

Contemporary external and internal views of the Royal Cobourg

Contemporary external and internal views of the Royal Cobourg

Although Mrs Grossmith continued to try to thwart the attempts of those who were keen to put William on the stage, after a while the Grossmiths were eventually persuaded to allow their son to give a full evening performance at their local theatre – an event which consisted of short acts featuring different Shakespearian characters, interspersed with comic songs. So impressed were the Reading audiences with the young Grossmith, that William and his father eventually set off on a tour of the provinces, along with an elaborate portable stage which had been specially constructed to accommodate the boy’s small size. William even found time to give a private performance to the Princess Augusta at her home in Frogmore Lodge, in Windsor, as well as to perform at the Chertsey residence of Mrs Fox (Elizabeth Armistead) – the elderly widow of Charles James Fox, the famous Whig politician, and a controversial figure, who in her youth had also appeared on the stage.

William Grossmith as Richard III in the Tent Scene (c)V & A Museum

William Grossmith as Richard III in the Tent Scene (c)V & A Museum

The childhood memoirs of young William draw to a close in 1827 with the grand announcement that the New Argyle-Rooms (off Regent Street) in London are booked for his appearance during the upcoming season, in an attempt to woo the fickle West End audiences. Thus the booklet ends on this positive note for William’s future success: . . . it may be confidently predicted, that, whether our very youthful actor should stop short at the point of histrionic excellence he has already reached, or whether ( . . .) he will be too conspicuous and remarkable not be generally observed, and his beams too pure and splendid not to be constantly admired.

However, by 1830 not only had the New Argyll Rooms ceased to exist, having burnt down in a fire, but with William now an adolescent (the playbill appears to have taken some liberties with William’s real age), his ‘Farewell Tour’ had already been announced (see playbill above). The playbill (below) of the following year ushers in the new infant prodigy: William’s younger brother, Benjamin Who is now but five years and four months old. It is interesting to note that a later newspaper advertisement from 1833 indicates that the two Grossmith brothers are still occasionally acting together, so perhaps it was not quite as easy for the teenage William to relinquish his fame (and fortune). And in fact a further discovery (while making a final edit to this chapter) showed that the two brothers had indeed continued to act together throughout the 1830s, touring Scotland, Cornwall and Ireland, albeit with William still having the lesser role.

Playbill feat. Grossmith brothers, 1831 (c)V & A Museum, London

Playbill feat. Grossmith brothers, 1831 (c)V & A Museum, London

The young William’s slip from top billing is perhaps unsurprising. In the history of the theatre, very few juvenile actors have ever enjoyed the same level of success as adults – to wit, the young Master Betty, who gave up acting when he went up to Cambridge at seventeen, but after an unsuccessful comeback was forced to retire at twenty and live from the wealth he had accumulated in his youth. Perhaps our William was lucky in that from an early age he also showed a great interest in things of a scientific nature. In the latter biography of his childhood it is remarked that during his country-wide tours he would often collect fossils in his free time, and when visiting the north of England it was reported that: Nothing in this quarter engaged the boy’s attention so much as the mode of weaving cotton by the vast powers of steam, so multifarious in its application.

Two years earlier, in 1825, the writer of his first biography also mentioned that, alongside his powers of mimicry, a genius for poetry and song, and appreciation of art and architecture, the young William is equally as curious in scientific and mechanical acquirements. He views minutely all kinds of machinery, he enquires and examines into its nature, its use, and its properties; a mere cursory inspection will neither gratify his senses, nor satisfy his enquiring mind; everything must have its explanation, for he observes, “everything has its use”.

Although William Robert Grossmith was obviously interested in things of a mechanical nature, we do not know how his conversion from child actor to mechanical surgeon was achieved: most likely he took up some course of study or apprenticeship in his teens, which he may have combined with intermittent touring. Unsurprisingly, it would seem that Emma’s stepfather showed the same sort of devotion to the craft of creating artificial limbs as he previously did to stage acting. In the book describing this successful second career, published when he was but thirty-nine, (after fourteen years of running the business – and of marriage to Emma’s mother), he outlines at great length how to construct the perfect limb for different types of injuries.

Although it makes for slightly gruesome reading, it is fascinating to note (from the case histories of past patients) how many people at that time lost limbs in the employ of the new steam railways – in addition to those that were amputated due to illness (often in childhood) and riding accidents. As Grossmith himself points out (and stated in the introduction to this chapter): It is an undeniable fact that the number of amputations performed in this and other countries has been greatly augmented of late years, attributable no doubt to the numerous accidents occasioned by the increasing use of Machinery and Steam power in all departments. This circumstance, in conjunction with the casualties of the late war*, have caused the subject to be brought prominently before the notice of the medical profession. * The Crimean War

Artificial leg by William Grossmith (c) Science Museum, London

Artificial Arm, by William Grossmith (c) Wellcome Collection, London

Artificial Arm, by William Grossmith (c) Wellcome Collection, London

In 1856, William Robert Grossmith was granted Freedom of the City of London by redemption (meaning that he possibly paid for the privilege). However, by the mid-nineteenth century the advantages to being a Freeman were not as great as they had once been, and perhaps William was more concerned about the status this honour would confer on him than anything else. In the frontispiece to his book on amputations, he dedicates the work to William Lawrence, president of the Royal College of Surgeon’s and a leading ophthalmic surgeon of the time, who also treated Queen Victoria (and was made a Serjeant Surgeon, or surgeon of the royal household). In this dedication, Grossmith mentions the many patients which this eminent surgeon had sent to his business in Fleet Street, and praises him for his promotion of the advancement of the Industrial Arts. So it is perhaps while writing the book that he decided to apply for the Freedom of the City, an act which he may have reasoned would eventually lead to more professional kudos.

Not only did William Grossmith win the medal for artificial eyes at the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park in 1851, but accolades followed from several other international exhibitions, including the Great Industrial Exhibition in Dublin in 1853, and the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1855, where Grossmith won medals for his artificial limbs. These awards were always mentioned in the frequent advertisements for the business which appeared in the regular newspapers of the day.

After William died in 1899 (one year after his step-daughter Emma), the business survived well into the 20th century with the name W. R. Grossmith Ltd intact. Before William’s death the company had already moved its premises to 110 the Strand, then later round the corner to 12 Burleigh Street. Unfortunately, William’s immediate successor to the business – his son, William Benjamin – had died almost twenty years previously at the age of 30 (while working for the company), and William Grossmith’s step-son John Henry Sleath (Emma’s older brother), who had initially been apprenticed to the business as a Surgical Mechanist, had eventually taken a different professional direction. (His other step-son, George Sleath, who had worked for the business had unfortunately also died relatively young).

When William made his will in 1887, he had still not specified who would take over the company on his death – mentioning a codicil he intended to make to clarify this. This was, however, never written and it has so far proven impossible to find out what happened to the firm after William’s demise. I am, however, convinced that such an astute business man would have organised his succession planning before his death at the age of eighty-one – particularly as the business was still limping on (no pun intended) even after I was born! But after two centuries of trading, the company of W. R. Grossmith finally went into liquidation – an event which took place in 1966 at their registered office in Africa House*, Kingsway.

*Observant readers may recall that it was in this very building, less than twenty years later, where I started my career as a genealogist (see The Incidental Genealogist is Born).

Over the two hundred years that the company sold trusses and artificial body parts, it moved between owners and addresses (mainly all in Fleet Street), although the Sleath connection was the thread which continued to run through the company’s history. When Emma’s father (John Henry Sleath) took over the business as a young man, he himself had inherited it from a Mr John Williamson, his father’s business partner – who, in a strange coincidence, had also become his step-father. So perhaps when John Henry Sleath later took on the young William Grossmith he had in mind the possibility of the very same role for him. Certainly the speedy way which Emma’s mother remarried (already called Mrs Grossmith when the will was finalised) makes one think this scenario was not unlikely.

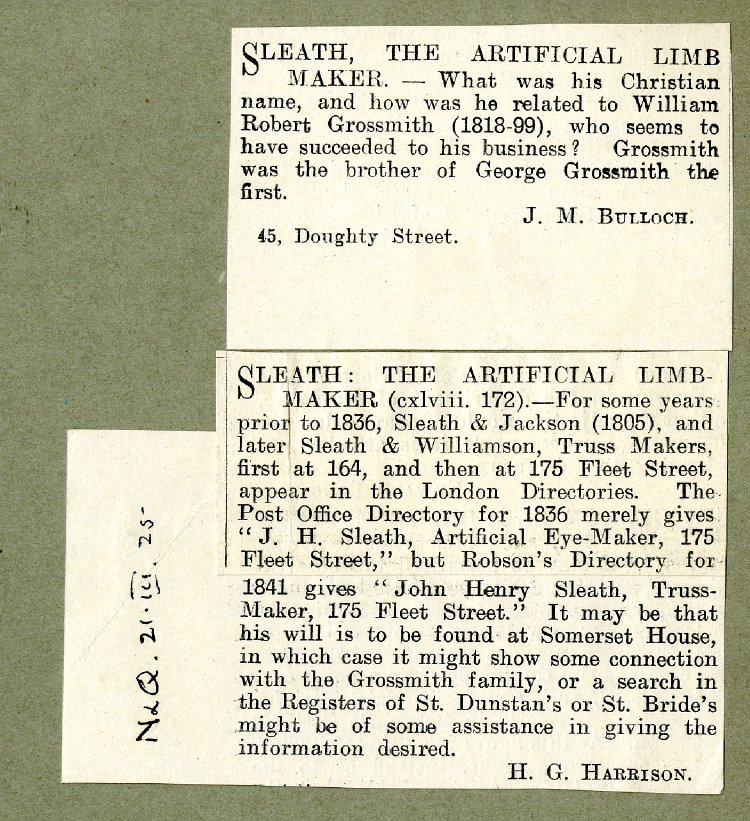

Interestingly, a couple of years ago an online search alerted me to a letter in a 1925 edition of the journal Notes and Queries which asked about the relationship of William Robert Grossmith to Sleath, the artificial limb maker, but at the time I was unable to discover if anyone had ever replied to this rather unusual query. Then while putting the finishing touches to this chapter I unexpectedly came across both a copy of the original question – and the response – which I have included below.

(c)The British Museum, London

(c)The British Museum, London

John Henry Sleath’s will was indeed to be found, although it is no longer kept at Somerset House (a place I remember from my days as an heir hunter). With a credit card and an internet connection, the pre-1858 (Doctors’ Commons) wills can be ordered on-line instantaneously from the National Archives, and lately even the Probate Registry (for wills post-1858) has moved into online ordering, considerably speeding up research time.

John Henry Sleath’s simple and uncomplicated will (made in 1841, two years before he died) stated that everything he possessed should be given to his wife Martha, and appointed her his sole executrix. There were no caveats about remarriage (such as in my great-great grandfather’s will to his much younger wife, Mary Ann), and in the document Sleath stated that he entrusted Martha with his estate well knowing that she will do the best for our children. So it would appear that he regarded his wife as a trustworthy partner, and combined with the absence of financial restrictions on her remarrying, this may point to the fact that William Grossmith could well have been already lined up to step into John Henry Sleath’s shoes. And so it is perhaps fitting that it’s Emma’s step-father who should have the last say in this chapter, linking as he does the story of the Grossmiths and Emma’s actor-manager son, Herbert Sleath, who with his older Grossmith cousins, George and Weedon, on many occasions.

Last year (2016) was the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, and to mark the occasion the BBC created a Shakespeare on Tour website in which, to my delight, William Robert Grossmith was featured, using his early life to illustrate the history of childhood Shakespearean actors. This was mainly because of the discovery of old playbills (such as the ones above) which showed Young Master Grossmith touring in the north-east. (The link to the above-mentioned site is here and the link to the short recording of schoolchildren discussing Grossmith’s stage career in an acting workshop is here, and is an especially touching tribute).

However, it is interesting to note that the website states that: It’s difficult to find details of Grossmith’s life after he retired. According to an article in The Idler magazine of February 1893, the comic actor and writer George Grossmith, remembered today as the author of ‘The Diary of a Nobody’, claimed to be nephew of Master Grossmith the Infant Roscius. It seems that no-one can ever imagine the delightful child actor eventually becoming a successful maker of artificial limbs, hands, eyes, noses &C.

But perhaps one of the main things that unites the young William Grossmith with the older one, is a sense of playfulness. In an interview with the New York Times at a Surgical Aid Society meeting in London in 1889, not only did Grossmith mention how he can spot one of his ‘own’ legs walking down Fleet Street, but he also enthusiastically discusses the quality of his artificial eyes (which seemingly fill a prominent place in the window of his body parts’ shop). According to Grossmith, his artificial eyes (which he was proud to state were worn by MPs, actors and the clergy) will last much longer than those of his competitors due to the fact that they are made from durable French enamel. Despite this advantage, the technology was obviously still not available to create an unbreakable eye. I have one customer Grossmith starts, who uses 6 or 7 every year. He is a member of the Athanaeum Club, where there are marble washstands, and is constantly letting his eye drop on these and break when he takes it out with the object of cleaning it.

See you next month!

The Incidental Genealogist, April 2017

A fascinating post- I am researching some of the deceased buried in Brockley & Ladywell cemeteries -SE London . One grave of interest is that of a Henry Robert SLEATH ( died 1930 aged 29 yrs) Could he possibly be a relation?

Regards

Mike Guilfoyle

Vice -Chair Foblc

LikeLike

Thanks for getting in touch. I’ll get back to you next week via email about Henry Robert Sleath after I’ve carried out some research. Not sure yet if he is related.

LikeLike

Hello, I have been fascinated to read about the Sleath connection with artificial eyes. We are descended from Rebecca Sleath(1809-1877) who married Henry William Richards. The Sleath name is very new to me. My Father was one of the few Contact Lens Practitioners in the 1950’s working for Obrig. He also did Hospital work with artificial eyes and cosmetic lenses around the Uk and Canada. He is a Liveryman of the City of London.My Grandfather ,Francis Hugh Touhey was an optical lens worker,born Islington. I do not know how he got into optics but it is amazing to find this link.I would be interested to find out more of the Sleath-Richards.

Best wishes,

Kevin Touhey

LikeLike

Great to hear from you. Not sure if Rebecca Sleath is a relative but there could be a link there. I’ll respond to your email in more detail once I find out more.

LikeLike

Thanks for your reply. I will look forward to it.

LikeLike

Just in case you are interested – from a book I am writing about York:

28 September 1833

Benjamin Grossmith, a child of six year, performs twelve different characters in his Adventures in the Reading Coach at York’s Theatre Royal. He is assisted by his older brother, William, aged fifteen. They acted in “a little movable Theatre, which was fixed in the middle of the ordinary stage, … a very ingenious contrivance, the size of a proscenium bearing such proportion to the height of the juvenile actors as to make them appear much taller than they really are.”

The previous month, on 2 August, “Master B. Grossmith, the celebrated juvenile actor, of Berks (now but six years old!)” had appeared at the Theatre Royal Beverley in a show that was advertised as an “Unequalled Display of Precocious Talent Aided by Fifty Changes of Splendid Dress and Scenery … The Diorama of Shakespeare’s Jubilee will be presented”.

Master William became a mechanical surgeon working in prosthetics, and Benjamin went on to become a missionary. Their younger brother George was the father of Weedon Grossmith.

(Rosenfeld 2001:238)

LikeLike

Thanks so much for this – it’s great to get any extra information from other sources and I’m fascinated by the story of these boy wonders! I had not known about Benjamin becoming a missionary.

LikeLike