By the cloisterly Temple, and by Whitefriars (there, not without a glance at Hanging-sword Alley, which would seem to be something in his way), and by Blackfriars-Bridge, and Blackfriars-road, Mr. George sedately marches to a street of little shops lying somewhere in that ganglion of roads from Kent and Surrey, and of streets from the bridges of London, centering in the far-famed Elephant who has lost his Castle formed of a thousand four-horse coaches, to a stronger iron monster than he, ready to chop him into mince-meat any day he dares.

Charles Dickens, Bleak House (1853)

As regular readers may remember, when my great-great grandfather, James Skelton, finally got round to marrying his much-younger second wife, Mary Ann Hawkins, in 1864, the couple had been together for over a decade and presided over a family of six. However, when James Skelton died only three years later, shortly after his 68th birthday, his will stipulated that his estate should be divided up between his wife and four children. As mentioned before (see Where there’s a Will . . . and the Sun), it was the two oldest boys – William and James junior – who were not named in the document. In the case of William it is perhaps unsurprising, as all evidence points to the fact that he was not James’ son. And although I have never been able to confirm the death of James Skelton junior, his absence from any records after the 1871 census (where he was living at home in Aldred Road with his widowed mother and younger siblings) makes me suspect that he most likely died as a young man.

I would very much like to be proven wrong, though, and every so often make another valiant search for him, never giving up hope of finding a middle-aged James Skelton jnr somewhere – perhaps running a garage, or working as a dodgy builder/decorator (two career choices his younger brothers made). But while my search for the elusive James has drawn a blank, in the intervening years I have discovered more about the other child who was not mentioned in the will – his older half-brother, William Hawkins Skelton – and the boy I sometimes think of as the black sheep of the family.

I have yet to come across any records of William’s birth: he suddenly appears as a fully-formed infant with his unmarried mother in the 1851 census. Frustratingly, Mary Ann is not at home on the day of census (the last weekend in March), but is described as a ‘visitor’ to a house in riverside Lambeth where an oil man called George Tiltman and his young family live. The Tiltmans, however, have a servant who is the same age as Mary Ann. Could this be the reason she is at their house? More plausible, perhaps, than the theory of one of William’s descendants: that the Tiltmans may have been philanthropists who took pity on a young, impoverished single mother. I do feel that this may be putting 21st century sensibilities into mid-19th century heads, and that it is unlikely that Mary Ann would have lived with the family without playing some sort of functional role in the household. Interestingly, The Society of Genealogists points out on their website that: Apparently unrelated household members noted as visitors or lodgers, and sometimes servants, may in fact be members of the extended family. Their surnames may give clues to in-laws or marriage partners. This is also the case when in-laws are specifically recorded.

While that has certainly been true with other ancestors (see A Rose in Holly Park), I have found no familial connections to the Tiltmans. To complicate matters further, at the time of the census Mary Ann was already two months pregnant with her second child, James junior, who was born in October of that year. The official birth certificate declares her address to be 83, Waterloo Road, Southwark (a stone’s throw from the Tiltman residency), but does not name the child’s father. However, as mentioned in an earlier post (see When I Grow Rich), the spring census states that two unmarried ‘tailoresses’ were living at this address, which could point to the fact that Mary Ann (described in later records as a ‘needlewoman’) was lodging with contemporaries.

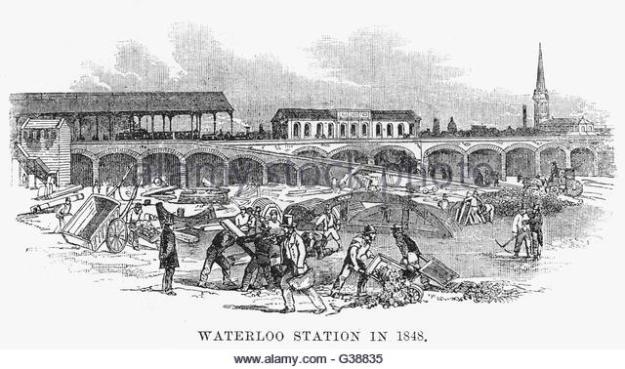

As I have previously pointed out, this line of reasoning does of course open up speculation as to whether the young women, including Mary Ann, were indeed what they said they were. Waterloo Road and environs was not exactly a salubrious area – and the coming of the new Waterloo Bridge Station (with its ‘iron monsters’ that Dickens alludes to when describing Mr George’s foray over Blackfriars Bridge into South London in the passage from Bleak House, above) did little to improve the neighbourhood.

Constructing Waterloo Bridge Station when Mary-Ann lived nearby

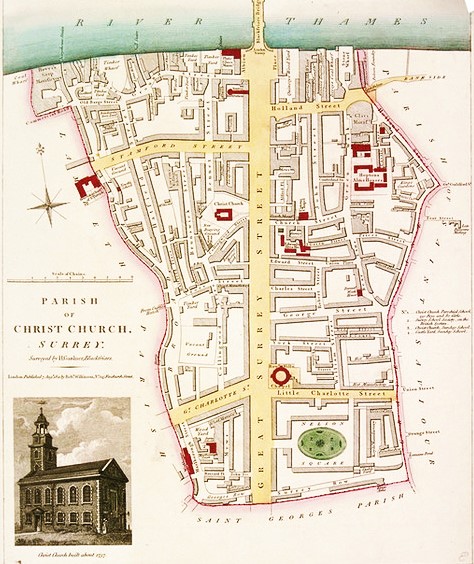

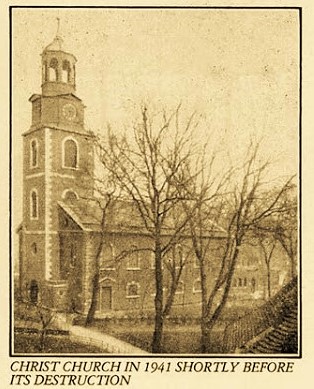

So William’s start in life is shrouded in mystery, although I think it is safe to say that he was not James Skelton’s child. The only consistent ‘fact’ about him is that throughout his life he names Christ Church, Southwark (sometimes erroneously giving the location as Blackfriars, Surrey – perhaps because the church is on Blackfriars Road), as his birth parish. I have noticed that many of my ancestors always remembered the exact London parish where there were born, however small, yet often make ‘errors’ with other facts. It seems strange that they never forgot this throughout their lives, despite many of them constantly being on the move from a young age, and indicates the bureaucratic links that the inhabitants had with the parish of their birth. Unfortunately, many of the parish records of Christ Church were destroyed along with the old church in a bombing raid, in April 1941, so there is no way of knowing if Mary Ann took her infant son to be baptised at the church.

Christ Church c1800 (Great Surrey Street became Blackfriars Rd)

William Hawkins Skelton was most likely named after his maternal grandfather, William Hawkins snr, and it was his younger half-brother James junior who had all the honour of being James and Mary Ann’s first born. However, despite this, William was soon part of the growing Skelton-Hawkins family and in the 1861 census he can be found as an 11 year-old schoolboy living at 35 Aldred Road (where the family were to stay for almost half a century) along with Mary Ann and James snr, and three half-siblings. Ten years later, in the 1871 census, he was at the same address (now minus his elderly stepfather, but with yet another half-brother), and in 1881, at the grand old age of 31, the census records him again as being unmarried and still residing at Aldred Road. It is not until the following decade that we find him with a family of his own: wife Annie (ten years younger) and three young children. By the turn of the century, four more children have arrived and William gives all the impression of a settled, middle-aged, family man.

But things are often not what they appear. When relying on census records it is easy to forget that they are only brief snapshots across the decades (see Moments in Time) and many events can take place in the ‘hidden’ years between. Not only that, but for various reasons a certain percentage of the population were tempted to be less than truthful about their situations. To wit, William’s own mother, who, in 1861 was described as being a widow with five children and working as the housekeeper/servant to the retired widower, James Skelton. Of course, it was all those children which gave the game away. After all, what elderly man would employ a live-in help with an accompanying brood of five when a single woman, unencumbered by a young family, could just as easily have filled the vacancy?

And so it should not have been a surprise to suddenly discover that, between the ages of 21 and 31, our William slipped out of sight to marry and have a family of four, then leave his wife to return to his mother in Kennington. It seems such a modern story, and yet there is a horrible twist to it. It would appear that once William left his wife, some of his children assumed William to be dead – or regarded him as so. And thus it came to pass that when his oldest daughter, Alice Margaret, married as a teenager in 1894, her father was officially recorded as a deceased painter/decorator. For those of us who have experienced the loss of a parent while relatively young, this revelation may come as an ugly shock.

I still remember that powerful episode of East Enders (from my soap-watching days) when ‘Dirty Den’ came back from the dead and his daughter Sharon was confronted with the awful truth of what her father had done. The story focused on the conflicting emotions which ensued, and I can only imagine how William’s daughter would have reacted had she come across her supposedly deceased father on the streets of Southwark, especially if she believed that both her parents had been complicit in the deception. And who has not lost someone close and had the terrible (recurring?) dream where the person in question is not only found to have been alive all along, but is in fact discovered living nearby?

In the summer of 1871, just three weeks after the census showed the twenty-one year old William living at home and uncharacteristically working as a school teacher (possibly one of those untrained teaching positions which helped to maintain discipline), he married a widow, 12 years his senior, at the local registry office. What his mother thought of this situation is anyone’s guess, particularly as William’s new bride already had a young family of four – although Mary Ann did agree to be their official witness. Despite the fact that Elizabeth Sarah Chappell (née Sparks) was then already pregnant with their first child (a boy named Arthur William), she was only one month into her pregnancy, and most likely not even aware of it herself. So I do not believe that was the reason for their marriage. But what I imagine to be more likely is that this older, recently widowed woman, already experienced in the ways of ‘married love’, was perhaps very appealing to the young William, who may have found life rather suffocating at home with his mother and teenaged siblings. He might have even still felt alienated by the absence of provisions for him in his stepfather’s will, three years earlier. And at twenty-one, he no doubt gave little thought to the future of the four fatherless children he had suddenly ‘inherited’ with his marriage.

The unexpected union of Elizabeth and William produced a further three children of their own, and then in 1881, when William is to be found back at Aldred Road under his mother’s wing, Elizabeth appears on the same census with five of her seven children, and describes herself as married – living apart from husband. But before long she is back to calling herself a widow, although (as expected) she keeps her new married name of Skelton. So something which might have started out initially as a misunderstanding – that Mr Skelton is the deceased husband (rather than Mr Chappell) – eventually becomes the family line. And in 1891, up pops William again in the latest census with his new ‘wife’ Annie Skelton (née Lipsham) and another set of children, so Elizabeth would have possibly had no choice by then but to officially call herself a widow (as divorce was only for the very wealthy).

Even on her mother’s death in 1920, Elizabeth’s oldest daughter from her first marriage describes her as Widow of William Skelton, House Painter (Journeyman). As William did not die until five years later, either she believed her mother’s story or was complicit in the lie. Another scenario is that William (or a family member) tricked the Chappell-Skeltons into believing that William had died at some point – although this idea does seem rather far-fetched. But it is of course also possible (and more plausible) that everyone in the family knew he was alive and living with another woman, and just kept quiet about this fact to satisfy the authorities. One day I hope I will eventually find out the truth about William!

When one of William’s descendants contacted me a couple of years ago, he confirmed what I had expected about William’s second ‘bigamous’ marriage. And even more excitingly, he was able to supply extra details about William’s first family by telling me the story of his own great-grandfather, James Frederick Skelton. Born in 1873, in Bethnal Green during his parents’ short sojourn out of south London, James was the 2nd of William’s children with the widow Elizabeth Chappell (the first being Arthur William). When James was born, his father’s profession was described as a Tramway Car Conductor. Interestingly, while William had described himself as a Gas Fitter on his marriage certificate, as previously mentioned he was said to be a School Teacher on the 1871 census several weeks earlier, a Journeyman Plumber in early 1872 (when Arthur William was born), a General Labourer in 1881 (when he was back at Aldred Road briefly). And for the latter part of his life he oscillates between a House Decorator and a House Painter, often adding that wonderfully elusive Victorian & Etc. I don’t doubt he did all these things (and more besides), but it does give the impression of a risk-taking or ‘entrepreneurial’ spirit – the kind of man who might easily have had two wives!

In 1906, William’s son, James Frederick, married a heavily-pregnant local Brixton girl, and his sister, Alice Margaret, and her husband were the witnesses at the wedding. However, unlike on Alice’s marriage certificate, there is no mention of his father William being ‘deceased’. Three weeks later James Henry Skelton was born – the grandfather of the ‘long lost cousin’ who contacted me, and the first of nine children the newly-married couple would have together.

James Henry (or Jim) lived a long and fruitful life, not dying until 1990. His descendant, Mark Coxhead, told me that at one stage an uncle agreed to undertake family research for the old man, but that his grandfather declined the offer. Mark had always believed this was to do with him being born only a few weeks after his parents’ marriage in 1906, but had later wondered if it might also have been connected with the ‘bigamous’ situation of his grandfather William’s so-called second marriage. However, I think it is more likely that the old man did not want the past raked over in the off-chance that, like many of his generation, something distasteful – and perhaps still unknown – would be found lurking in the woodshed (where old branches of the family tree were stacked).

Nowadays, we all thrill to family histories which include illegitimate births, criminal records, workhouse and asylum admissions &Etc. But trawl not too far back and most of those born at the turn of the previous century were not so keen to go prodding about in the closets of their past. Victorian sensibilities died hard, and 20th century families were still afraid of ‘scandals’. So it is not surprising that as one neared the end of life it would have been more comforting to let the past remain there, particularly after the upheaval (physical and mental) caused by two world wars, which may have also resulted in the loss of family members. As Mark pointed out, although his grandfather had served in WW2 he never talked about his wartime experiences. Like my own grandfather’s service in the Hussars in the Great War, no-one in the family knew what he had witnessed – and I have explored the ramifications of this silence in more detail in a previous post (see Of Lost Toys and Mothers).

It would seem, though, that small skeletons have indeed tumbled out of their respective cubby-holes. Records show that both James Frederick and his older brother, Arthur William, spent a large proportion of their young adulthood in the pre-war WW1 military (as my own grandfather did), joining different regiments in the 1890s, and both were sent to India for most of their 12 year stint in the army. (My grandfather was also said to have been in India before the Great War, although like many who served at that time his army records were lost during WW2 bombing). James and Arthur were both discharged in 1905 – just in time for James to marry, start his family, then re-enlist with his brother at the outbreak of war in August 1914 (when both were relatively old for active combat, although obviously experienced as soldiers). The two Skelton brothers were discharged in 1918, shortly before the end of the war.

The ‘family skeletons’ which arise from the military records are certainly not scandalous, but paint a colourful picture of William’s oldest sons, in particular Arthur William. Not only does he seem to consistently lie about his age on his enlistment forms, but throughout most of his Indian service Arthur is found to be repeatedly disobeying orders. His conduct sheets include the following remarks: Drunk and improperly dressed returning to barracks; Absent from Tattoo; Neglecting to obey station orders – being out of bounds.

As punishments for these offences he is confined to barracks, endures detention, and is fined several shillings. He is promoted then demoted, but despite all this his character is described as good on his discharge forms. I do not know what happened to Arthur William after he returned to civilian life, but he does not seem to have favoured marriage and family life, like his brother. For his part, James Frederick, while never drunk on duty, is often heftily fined, as well as being punished with month-long detention, for being AWOL. I was also fascinated to learn that both brothers enter the army with tattoos on their right arms: Arthur a cross; James a heart and flower (details which could only be gleaned from the army records). Oh, what I wouldn’t give to have such information from my grandfather’s time in the military!

Arthur & James Skelton in tropical uniform (c) Mark Coxhead

It is interesting to note that when both brothers join the army in the 1890s, they give their father, William Skelton, as their next-of-kin. When re-enlisting in 1914, however, James Frederick names his wife and children, while the unmarried Arthur lists his mother and sister (Alice Margaret). Thus it would seem that William Hawkins Skelton was at least in contact with his sons while they were younger. Perhaps a better theory than those I have previously suggested is that William was regarded as ‘deceased’ by the members of the family who were angered by his domestic arrangements, and not by those ones who (grudgingly?) accepted his lifestyle choice. I certainly know of one or two modern families where such things have happened, and the phrase he/she is dead to me can still be heard today. Interestingly, it is only the female relatives who describe William as ‘deceased’ – which is also concurrent with theories that women are generally more concerned about social status and ‘keeping up appearances’ than men.

The other curious fact is that Mark’s grandfather seemed to be adamant that red hair was a Skelton family feature. However, as Mark himself points out, this could have come from any side of the family, if it indeed was an inherited feature at all. But the only relative that our two families have in common is Mary Ann Hawkins, so any particular shared trait would have had to have been passed on from her. My grandfather did have a brother James (who died in WW1) who was nicknamed Ginger on account of the colour of his hair, but to believe that there was a genetic connection involved does sound more like an instance of wishful thinking. As indeed does the other family trait that Jim Skelton seemed to have inherited: namely that of an ‘unpredictable’ nature.

In 1960, after working in the Southwark-based Warehouse Department of Fleetway Publishing for four decades, James Henry Skelton was finally made Warehouse Manager, an event that was recorded in the in-house staff magazine. Mark sent me a copy of the article, which also includes a photograph of the fifty-four year old Jim Skelton (who started at the firm as a fourteen-year old sweeping-up boy when his father, James Frederick, worked there as a porter after the war). The text states: As a fiery auburn-haired boy at Lavington Street back in 1920 under his father’s watchful eye he experienced much of the rough and heavy days that were then part and parcel of healthy circulations. The article then goes on to say that: From those encounters, perhaps, he developed the art of creating a practical joke while maintaining a poker face. Later it is rather cryptically pointed out that: While much of the impetuous fire may have been calmed by maturity, and ‘storms’ now subsided in teacups, the very nature of his varied tasks in a department becoming more technical than ever before must inevitably find Jim Skelton being accepted by different groups in different ways. Hence he may continue to be a controversial figure: which may turn out to be far more interesting than putting him in a definite category.

The accompanying picture shows Mr. J. H. Skelton squinting at the camera in a way reminiscent of my father, my grandfather and his brother Arthur, and also their father, Arthur snr (William Hawkins Skelton’s half-brother). So did those deep-set drooping eyes actually come from the Hawkins family? And if so, can they really be claimed as a ‘Skelton trait’? Perhaps more interesting are the hints that Jim had a ‘fiery’ personality – something that could be said of my grandfather and his brother Arthur and some of their descendants!

The accompanying picture shows Mr. J. H. Skelton squinting at the camera in a way reminiscent of my father, my grandfather and his brother Arthur, and also their father, Arthur snr (William Hawkins Skelton’s half-brother). So did those deep-set drooping eyes actually come from the Hawkins family? And if so, can they really be claimed as a ‘Skelton trait’? Perhaps more interesting are the hints that Jim had a ‘fiery’ personality – something that could be said of my grandfather and his brother Arthur and some of their descendants!

When I started my research in 1984, Jim Skelton was still very much alive, and possibly enjoying a full retirement, pursuing his love of gardening, collecting wood, literature and classical music (all hobbies he was doing in 1960). Frustratingly, had I then all the information currently at my disposal, it might have been possible to ask him about his shadowy grandfather. (Did you ever meet him? would have been my first question). But perhaps this would not have yielded up as much information as I like to imagine. I have previously managed to make contact with the surviving grandchildren of other Hawkins-Skelton offspring and disappointingly it is often impossible to get beyond a tantalising Yes, I remember the old man or The families lost touch after the war, and it feels impolite to keep pressing an elderly stranger who may become distressed at bringing up the past.

Yet I still nurture this wild hope that some distant relative out there has a box in their attic which, while not necessarily a receptacle for skeletons, might be hiding a bundle of letters and some photograph albums, or even a diary or two. When I hear about other such genealogical finds, I feel myself twitching with envy, and wondering whether this holy grail of family history might ever be mine – or whether I am doomed to be like the gold panners whose finds of a few shiny flakes encourage them to persevere in their quest, ever hopeful of discovering a nugget.

But perhaps it is the very conscious act of putting flesh on the bones of such a meagre skeleton that forces me to reach out beyond my own family history to seek out parallels and stories from the wider world. And so it is that I have come to believe that it is the existence of Blackfriars Bridge which, by linking the two riverside parishes of St Ann’s and Christ Church, united the Hawkins with the Skelton Family, and which may also have accounted for William’s confusion in regard to the location of his birth parish.

My great-great grandmother, Mary Ann Hawkins, was born in the shadow of St. Paul’s, and spent her childhood in the dingy courts and alleys of the City parish of St Ann’s, Blackfriars (named after the site of the medieval Domenican riverside monastery of dark-clothed monks). This was a parish without a church after the building was burned down in the Great Fire in 1666, and was afterwards amalgamated with St Andrews-by-the-Wardrobe – even though it continued to keep separate parish records. And more importantly for our story, it was considered the ‘home’ parish of the Hawkins, and the place where Mary Ann’s father, William Hawkins, unsuccessfully tried to obtain settlement relief, based on the fact that his own father had undertaken a seven year apprenticeship there.

Old Blackfriars Bridge from Lambeth, c1800 (demolished 1864)

Old Blackfriars Bridge from Lambeth, c1800 (demolished 1864)

Although the Thames was a physical and psychological barrier for most Londoners, living in one of the few parishes with a crossing to the other shore must have made movement to the opposite side more convenient and tantalising. And when I look at the above image of the old bridge (whose elegant Portland stone arches are perhaps already beginning to crumble), I can imagine the young Mary Ann scurrying across from the Middlesex-side, holding on to her skirts and bonnet as the wind whips upstream, while the river below her seethes with life and noise. Like her contemporaries (including the fictional Mr. George), she would have considered it normal to walk the streets of the capital for miles and whether she first crossed to the Surrey-side for business or pleasure or simple curiosity, she certainly could never have imagined that over a century later hundreds of her descendants would have made their home in ‘London over the river’.

The Incidental Genealogist, February 2017

Thank you for another thought provoking blog. Really it is all about truth and lies and secrets. We expect our ancestors to be as truthful as we think we are ourselves, but evidence might prove otherwise. Evidently in the 1881 census there were 61,000 more wives than husbands ! And certainly some women were creative with the term widow. So a motive for untruthfulness and secrecy was respectability. But your investigation shows that household formation was fluid and not so different from some sections of society today.

LikeLike

Thanks Marion for your response. Family history research is so often like detective work in the way it attempts to get at the truth. There’s looking at evidence from different sources, ‘listening’ to witnesses, and then trying to work out the answers from your own (and others’) knowledge about the world. It’s a constant learning curve!

LikeLike

A very interesting read especially as my father was a Skelton born in Lambeth.

LikeLike

Maybe we are related, but Skelton is/was not too uncommon a name in London – although not common either, as it comes from Yorkshire originally.

LikeLike