At its best, family history is a trespasser, disregarding the boundaries between local and national, private and public, and ignoring the hedges around fields of a academic study; taking us by surprise into unknown worlds.

Alison Light, Common People: The History of an English Family, (2014)

Later this month I will be holding a creative writing workshop in Switzerland (where I currently live and work) for teachers of English as a Foreign Language (EFL). The aim of this half-day workshop is to show teachers how they can use creative writing exercises in their EFL classes in order to encourage their students to take risks with the new language and to personalise it, thereby fostering a sense of ownership and increased confidence in the use of English. The teaching material is designed to be adapted for different levels of language ability, although the workshop will be aimed at native speakers. This is to allow the teachers to experience the activities as learners themselves, enabling them to tap in to their own creative wellspring.

My interest in family history and the demographic of the group makes it an obvious choice of topic for some of the exercises. For that reason I decided to focus this month‘s post on the different ways in which family history research and creative writing can be combined. To this end, I have adapted some of the activities used in the workshop to focus solely on family history. These exercises may be of interest to other writers and teachers*, as well as those who would like some creative inspiration to help them write their own family history.

*I use this term broadly as it may include teachers of others subject, such as social history.

Family Photographs

I have touched on the role of photographs in family research in an earlier post (see Those Ghostly Traces), in particular in relation to Susan Sontag’s On Photography and Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. Both these important texts about photography attempt to get to the essence of what it means to take photographs and be photographed; to collect photographs and use photographs to document events and lives, as well as shape and frame (reframe?) memory. As Sontag points out: What is written about a person or an event is frankly an interpretation, as are handmade visual statements, like paintings and drawings. Photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire.

Photographs of people are an obvious choice for teaching material as there is a wide variety of activities which can be used in conjunction with images, from simple descriptive vocabulary to complex character bios, to investigating historical details. If students can bring in copies of a selection of their own family photographs, then the activity takes on a more personal and meaningful nature. Naturally, this topic needs to be handled sensitively, but discovering more about the backgrounds of the other students generally increases both cohesion and respectfulness of differences within the group.

A series of photographs in chronological order can be used to create an interesting narrative, such as the ones I have of my English grandmother, Edie, which cover 70 years of her life (see I Remember, I Remember). This makes an ideal longer project and could be used as the basis of a short biography. To illustrate this, I usually print out a selection of my own photographs on good quality A4 paper and insert them into plastic pockets. This allows them to be handled and prevents them from being regarded as ‘too precious’. The images* (below) illustrate the relationship of my own grandmother with her beloved oldest brother Tom, before and after the Great War. Such a series could create a jumping off point for a number of activities. *All photographs courtesy of Tom’s grand-daughter, Margaret Andrews.

After Father Died c1905: Edie and Tom, with Fred and Harriet

After Father Died c1905: Edie and Tom, with Fred and Harriet

Before Going to War in 1915: Edie and Tom with Harriet

Tom’s Marriage in 1917: Edie (back centre) is bridesmaid

Tom’s Marriage in 1917: Edie (back centre) is bridesmaid

Postcards from the Past

For family historians, historical postcards can be an important research tool. In a teaching situation, copies of the original can be made, or postcards can be mocked up from images in magazines or on the internet. Using such images in a creative way can be a powerful way to attempt to see the world as our ancestors did. For example, postcards of places that family members visited on holiday, or where they lived, can be used as a stimulus to write to someone else in the character of a particular family member. The image I have of Kennington Park in its hey-day is one that helps me to imagine how it might feel to have visited the place at the time my ancestors lived nearby – the gardens being such a contrast to the dull streets and factories of their neighbourhood on the other (wrong?) side of the park (see A Tale of Two Parks).

Postcard of Kennington Park c1900 (purchased on ebay)

Postcard of Kennington Park c1900 (purchased on ebay)

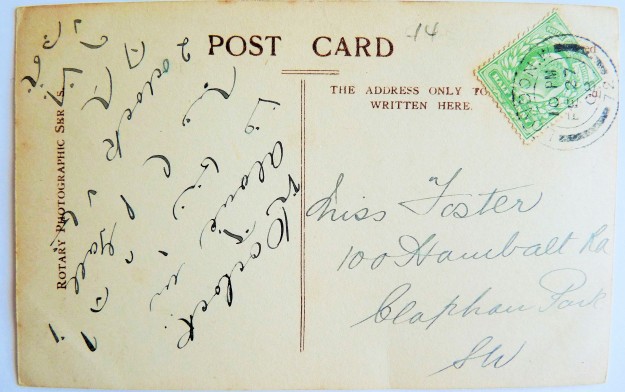

This activity could even be expanded to include postcards of people (ancestors or important figures of the time), such as the old Rotary ones of actors which can be picked up cheaply on the internet. I am currently amassing quite a collection of images of my Edwardian actor ancestor, Herbert Sleath and his actress wife, Ellis Jeffreys, and every so often purchase a used one where the writer might allude to the image on the front. I have even come across cards the couple sent to friends, and particularly relish one where Herbert appears to be arranging a secret rendezvous with another woman (written in shorthand) – a reminder of the days when the frequency of the postal service almost resembled the speed of texts and emails. Writing a ‘secret postcard’ could certainly add spice to this exercise. This activity could be expanded to write letters and diary entries in the character of an ancestor.

Did Herbert Sleath write this postcard (27/2/1908) himself?

Did Herbert Sleath write this postcard (27/2/1908) himself?

Secret Thought Bubbles

Continuing with the topic of secrecy, the first two activities lead naturally on to one where copies of portraits and paintings of people (usually reproduced on postcards) are distributed to the students, who then have to make up a ‘thought bubble’ for the person (or one of the people) depicted. It is interesting to then separate the writing from the images and ask the other students to try to match the ‘thought bubbles’ to the pictures. This is an activity I aim to do for the two portraits I have of the child prodigy actor, William Robert Grossmith (see Artificial Limbs on Curious Plans), stimulated by the discussion that the Sunderland schoolchildren had on the Shakespeare on Tour website (here) when speculating on his life. Obviously, this activity could be extended to include family photographs. I would also like to write thought bubbles for all the members of my family in the Skelton wedding photograph in the banner image above (reproduced in full below). I often wonder what little Peter at the front was thinking of the whole event!

My Grandparents’ Wedding, London, 1923 (c) M. Andrews

My Grandparents’ Wedding, London, 1923 (c) M. Andrews

Bringing the Past to Life

A couple of years ago I stumbled across these two silent film clips from the Mitchell and Kenyon collection of Local Films for Local People (now in the British Film Institute) which have been enhanced and set to a very evocative score. Whenever I feel a little lost for inspiration, or wonder if my genealogical quest is a worthwhile one, then I only have to watch these short films again to restore my faith in the value of my project. Such a clip can obviously be used in a myriad of ways in the classroom: from choosing to write about one of the people who appear in the film to creating descriptions and narratives (as well as ‘secret thought bubbles’). But perhaps more importantly, most people never fail to be moved by the lively scenes unfolding in front of their eyes, knowing as they gaze upon the curious and open faces that flit across the screen that not one of the population depicted in the film will be alive today. It is a sobering thought, but one that should spur us to action to make the most of the opportunities we have today to document the past lives of our ancestors.

Music of the Past

Although the video above is set to contemporary music (Chanson du Soir and Arco Noir from Richard Harvey’s Strings of Sorrow album), both tracks evoke the poignancy of the lost Edwardian world unveiled to us through the uncanny time machine of technology, and the music greatly enhances the viewing experience. Music in general can be made to stimulate ideas for writing and undertaking timed writing activities to various tracks is another way to unleash creativity. I often find I am drawn to listening to the music of the period about which I am writing: for example, The Lark Ascending by Vaughan Williams is one which is I find particularly inspiring when writing about the period set around the Great War.

The Things They Left Behind

Personal objects are an obvious way to build up a character bio. For example, writing a description of a person from a number of items that they carry around in their (hand)bag. This could include both something humdrum (e.g. a monogrammed handkerchief) and esoteric (e.g. an amulet). When my Scottish grandmother died and the flat in the sheltered house where she had lived for the last twenty years of her life was being cleared out, a strange crumpled little doll was discovered in her bedside table inside an out-dated Scottish Bluebell matchbox. I could not understand why she would have wanted to keep such a creepy-looking thing close by (particularly as so much had already been discarded when she made the move into sheltered accommodation) until my mother realised that it had been the decorative doll on her christening cake, over 60 years earlier. Such an object (and its discovery) certainly lends itself to a piece of descriptive writing.

Miniature Doll from my Mother’s Christening Cake

Miniature Doll from my Mother’s Christening Cake

What would they have said?

It is interesting exercise to attempt to recreate the conversations that our ancestors might have had with each other (and also with those outwith the family), particularly at pivotal moments in their lives. One day, while stuck for inspiration trying to imagine the lives of James William Skelton’s and Emma Sleath’s three children – the Sleath-Skeltons, who were born into a different class and lifestyle than any of the Skeltons who had come before them and any to come since – I wrote out a conversation the three of them might have had with each other as they took a walk round Hyde Park to discuss a matter of family importance. It was a tricky exercise that yielded up ideas that might have otherwise been rejected. And a reminder that even if the result never made it further than some lines on a piece of scrap paper, it still lodged itself somewhere in the imagination, sending out little shoots and tendrils of inspiration at unexpected moments.

Memories, Memories, Memories

Perhaps the most obvious – and powerful – type of creative writing exercise involves working with personal memories, however imperfect they may be. An exercise that worked well in a workshop I once attended is to imagine your grandparents’ old house while walking through it as a child, using all the senses as you do so. After this silent ‘meditation’ there is a timed exercise to put these recollections down on paper. Although the writing is often rough and ready, the raw material can later be worked on to come out with a memory that feels authentic, and which may unleash other reminiscences in its wake.

A similar exercise I undertook at another workshop is to write a description of a childhood incident in the 1st person, then once the piece is complete to pass it to another student to rewrite in the 3rd person – the other writer being ‘given permission’ to change some of the details if need be, usually naturally forming it into a tighter narrative in the process. This is a fascinating exercise on many levels, and it is particularly interesting to reread ‘your’ memory when rewritten as a short story, blurring the distinction between fact and fiction, something which can really lift a piece of writing. However, this exercise works best if you are not aware of what will happen to the text in the second part of the workshop!

The final ‘memory exercise ‘I would like to describe is one which returns to the initial theme of family photographs, and is from a practice called memory work that aims to bring to light repressed memories (and is thus a more private and personal exercise). As Annette Kuhn points out in her book Family Secrets: Anyone who has a family photograph that exerts an enigmatic fascination or arouses an explicable depth of emotion could find memory work rewarding.

The basic idea is to take such an image and start to describe it, moving from the obvious external cues to taking up the position of the subject (using the 3rd person), and attempting to bring out the feelings that may have been associated with the photograph. At the same time the context of the photograph should also be given consideration. So questions should be asked about why it was taken, where and by whom etc. In addition, attention should be paid to the technology used as well as the photographic conventions of the time. These guidelines stem from the work of artists Rosy Martin and Jo Spence, and encourage those undertaking memory work to be more critical and questioning of their lives and those of others. I have also found it also interesting to do this with other family members who may or may not also be in the photograph.

For myself I always feel strangely sad when I look at photographs of myself with my grandfather, Sidney Skelton (whose harsh beginnings I have written about in Of Lost Toys and Mothers). I never felt quite at ease when I was with him: I often could not understand his strange Cockney accent; his abrupt nature was disconcerting to me; his habit of permanently smoking strange-smelling roll-ups was off-putting to a young child. When I look at the picture (below) taken of us together at Ayr beach in the 1960s, I know that I am aware I have to pretend to love this taciturn English grandfather of mine as this is what is expected of me. Yet he is a stranger to me. And when he died when I was about ten (my first experience of the death of a grandparent) the only emotion I felt was a terrible sense of guilt that I was not able to be sad (wondering if that meant I would always be incapable of experiencing true grief).

With my grandfather, Sidney Skelton, Ayr c1966

With my grandfather, Sidney Skelton, Ayr c1966

But after recently enlarging the photograph to investigate it further, I could see there was more going on in the image than I had initially thought: the (most likely) painful burns on limbs which had been left unprotected from the sun (normal at that time), the small rag/towel that I am clutching for some reason – could it be to dry my feet? Suddenly I remember that I did not like going barefoot at Ayr seaside as the pink road between the beach and the low green was covered with a layer of very tiny sharp stones – but maybe Grandad had carried me over and deposited me on the low wall. So perhaps I am being too hard on myself, and there is no need to blame my miserable looking countenance solely on my grandfather (who most likely treasured the few occasions that he spent with his Scottish grandchildren). And I think about my father who might have found this photograph charming: his elderly father and first child, together in what was a typical family pose – although it does not seem to come naturally to Sidney, despite the fact that he looks happier than he does in other photographs from that time.

Later I discovered that the image was just one of a series taken on the same summer day at Ayr beach in 1966 (hard to believe this is half a century ago already!) I am currently arranging them into chronological order in an attempt to trigger more memories from that day at the beach, a fascinating experience that is yielding even more insights about this long-forgotten time in my life.

The Incidental Genealogist, May 2017