My condolences on the approaching departure of the daughter.

All sons-in-law are direct descendants of the Devil.

And the nicer they are the more devilish it is.

Rudyard Kipling to Sir Hugh Clifford, Governor of Nigeria, (May, 1925)

This new chapter in my family history is a stand-alone story that came as an unexpected surprise – a spin-off to the main narrative. It was, however, a fascinating tangent to my journey, and I would like to share the results with you in this month’s post. As August has been very busy with visitors here in Switzerland, I have been slightly restricted in my research time, so have chosen to present this vignette in the last remaining days of my summer break.

One of my recent visitors was my teenage nephew, who was taking a well-earned breather before his final year of A-levels. Despite the weather being constantly up and down (everything between 30 and 13 degrees), it was wonderful to have him ensconced in the spare room. I enjoyed playing the role of the magnanimous aunty, knowing I could spoil him in the relatively short time we had together. And as he winged his way back to Newcastle with a bag full of vintage Swiss Army clothing and chocolate bars, I could not help but wonder what life would be like if he came to live with us permanently. Then I would have to forgo my overindulgence of him and play the same role my sister has – one which inevitably comes with the onerous role of chief nagger, despite every parent or guardian’s best intentions.

This is exactly what Cecil Floersheim’s mother agreed to do when both her sister and brother-in-law died unexpectedly within two years of each other, leaving their little boy, George, an orphan at six years old. And in 1898, George Louis St Clair Bambridge (to give him his full name) was sent to live with the middle-aged Louis and Julia Floersheim at 12 Cadogan Square. By then their oldest son Cecil had just recently married my ancestor Maude Beatrice (see The Fortunate Widow), and although his younger brother and sister were still living at home they were already well into their twenties. Like his older male cousins before him, George Bambridge was eventually sent to Eton, and while the 1901 census finds him at home with the Floersheim’s in London, the 1911 census lists him as a boarder at the elite school. Coincidentally, George’s paternal grandfather – the photography pioneer William Bambridge – had been a schoolmaster at Eton in the 1850s before taking up the position of royal photographer.

George Louis St Clair Bambridge was the son of Julia Floersheim’s younger sister, Ada Henrietta Baddeley, and her husband, George Frederick Bambridge, who was the private secretary of Prince Alfred, The Duke of Edinburgh (Queen Victoria’s second son), later the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha – an appointment most likely obtained through his father’s post as photographer to Queen Victoria and her family. Julia and Ada Baddeley, who had four other siblings, were born in 1848 and 1851 respectively, and as the two oldest of the three girls (they had a much younger sister, Blanche) appear to have been close.

The 1891 census shows the newly married Ada Bambridge with the Floersheims and Louis Schott at Pennyhill Park (see On the Dogs’ Grave at Bagshot), while George Bambridge was with the Prince of Wales at the royal naval barracks in Devonport. This family get-together was possibly to celebrate Ada’s fortieth birthday – the census of 1851 had described her as a new-born female, as yet un-named. To my mind, this is a delightful piece of information which conjures up the insouciance of the upper and upper-middle classes when it came to the births of their children (all three of Julia Floersheim’s children were actually officially registered simply as male or female Floersheim).

The six Baddeley siblings moved around the country with their parents due to their father’s various army appointments. Major John Fraser Loddington Baddeley was from a military family, and was a decorated veteran of the Crimean War, where he had served in the light division. He had been present at most of the major battles in the conflict, before being badly injured at Inkerman. After this event, he was appointed second officer of the Royal Powder Works at Waltham Abbey for five years, later moving to the post of Assistant-Superintendent at the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield. He died there in 1862, at the age of 36, after contracting diptheria, and appears to have been a great loss to the army: his military funeral was conducted in style with large numbers of attenders. The obituary by the Institution of Civil Engineers states that: Lieutenant-Colonel Baddeley possessed all the qualifications for eventually attaining a very distinguished position. He had clear intuitive perception, good judgement, indefatigable industry, and had studied hard to extend his scientific and mechanical knowledge. To him may be ascribed the merit of the introduction to the service of the foreign mode of purifying saltpetre ; and he published a tract, ‘On the Manufacture of Gunpowder, as carried out at the Government Factory, Waltham Abbey (1857)’.

When Julia Frances Ellis Eva Baddeley married the thirty-five year-old Louis Floersheim in 1870, at the age of twenty-one, the marriage was considered to be good for the German-born (recently naturalised) immigrant’s social standing, due to the military record of the bride’s father. It has also been suggested that by choosing his wife from the Anglican Victorian ‘establishment’ Louis was also distancing himself from his Jewish roots, However, I cannot quite believe that this was such a calculated move. The young and beautiful Julia Baddeley was no doubt impoverished to some degree from her father’s untimely death and by then Louis had been established in London society and would have been seen as a successful older man. Interestingly, Julia’s two other sisters – Ada and Blanche – both married men over a decade older than themselves, perhaps searching for the father figure they had lost earlier in their lives.

Julia Floersheim (née Baddeley) c1870

Julia Floersheim (née Baddeley) c1870

In contrast to her sisters, Ada Baddeley married much later in life. The birth of George junior when Ada was forty-one might have come as a surprise to his middle-aged parents, and it is undeniably sad to think that this late-blooming romance was destined not to last more than five years – by 1896 Ada was dead, and two years later the young George lost his father too. (I have not yet been able to ascertain the manner of their passing, but both were away from home at the time: Ada in Brighton and George senior at Clarence House, St James, with the Duke of Edinburgh).

Without any siblings, it must have been a disorientating time for the young George, and although the Floersheims hired a children’s nurse and presumably cared for him as best they could, he would have had no ready playmates among his older cousins. And in a house where servants outnumbered the family by almost three to one, it might have been a rather strange and lonely life for one small child. Perhaps his later time at Eton was a relief to him. By then his foster parents must have seemed old and out of touch, and it is not surprising that he applied for a commission at the start of the Great War.

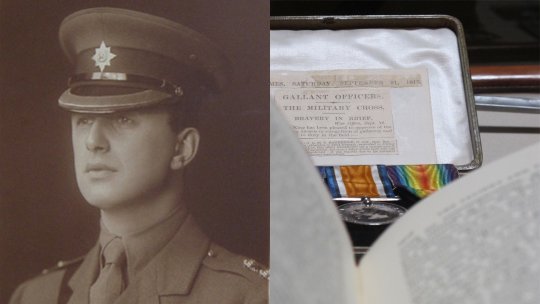

George Bambridge as a soldier (and his war medals)

George Bambridge as a soldier (and his war medals)

Bambridge went on to survive four years of conflict, winning the Military Cross for his bravery, and it was while in the Irish Guards that he made the acquaintance of Oliver Baldwin – the son of the future conservative prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, and cousin of the ‘Empire poet’ Rudyard Kipling. When Kipling lost his only son John at the Battle of Loos in 1915, he spent many years in what appears to be an atonement of sorts for his role in circumventing regulations that prevented his son from signing up for military service for medical reasons. (Whether it was the problem with his eyesight that lead to John’s untimely death at eighteen is open to debate). Part of working through this profound grief involved Kipling in writing a two-part history of the Irish Guards – John’s regiment – and being involved with the new War Graves Commission.

John Kipling (centre, in glasses) c1915

John Kipling (centre, in glasses) c1915

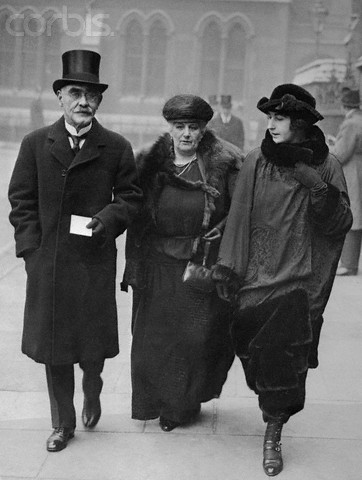

Thus Rudyard was delighted when Oliver introduced him to a young Captain in the Irish Guards one November at Bateman’s, the Kipling family’s Jacobean home in the Sussex countryside. Although neither Oliver nor George had fought alongside John (having joined the regiment later), Kipling was grateful for the extra insight they gave him into the life of a guardsman, and as Bambridge became more involved with the family, Rudyard increasingly began to regard him as a substitute son. This unofficial role had been the one assigned to Oliver Baldwin – before Kipling found out that, despite a short-lived engagement, his cousin’s son preferred the company of men. It is not sure whether Oliver and George Bambridge ever had a sexual relationship, but some biographers believe it was most likely, given that they travelled frequently through Europe and North Africa together.

Oliver Baldwin, with his parents, 1920s

Oliver Baldwin, with his parents, 1920s

However, at Easter 1922, Bambridge joined the Kiplings on their annual holiday to Spain, shortly before taking up a post as an honorary military attaché in the diplomatic service in Madrid. Kipling’s recent biographer, Andrew Lycett, writes that: With his knowledge of Spain and North Africa, George was an ideal guide to the once Moorish cities of Granada and Seville. He adapted easily to the expected role of the Kiplings‘ surrogate son, partly because he had been in the Irish guards and partly because his own parents were both dead and he needed a family. His father had been private secretary to queen Victoria’s second son, the career sailor Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, later Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. George’s childhood in the hierarchic world of minor courtiers had made him diffident, courteous and remote.

Elsie Kipling, with her parents, 1920s

Elsie Kipling, with her parents, 1920s

Lycett further points out that when George and Elsie announced their engagement early in 1924, the Kiplings were unhappy to learn that their last surviving child (their first daughter, Josephine, had died when young) would soon be leaving home, and Rudyard fell into a depression, not helped by increasing worries about his own health and that of his wife, Carrie. By then he knew about Oliver Baldwin’s homosexuality (which he kept from his wife and daughter). So it would seem that not only was he perhaps concerned about the suitability of Bambridge as a groom for Elsie from the perspective of his sexuality, but the Kiplings had always hoped to make a more wealthy and well-connected match for Elsie, who had a generous trust fund established in her name, and had been brought out in society at considerable expense.

In her fascinating biography of the four Macdonald sisters*, A Circle of Sisters, Judith Flanders mentions that: Bambridge was not a terrific catch. True, he was a young diplomat and he came from a good family – his father had been a secretary to the Duke of Edinburgh: with his family and Kipling’s money, anything was possible. However, his very close friendship with Oliver came under scrutiny when in the 1920s Oliver began to live openly with another man. (This was his long-term partner, Johnny Boyle). In addition, Oliver became a socialist in 1923 (and in 1929, briefly a labour MP). A socialist and a homosexual: Kipling never spoke to him again.

*Alice MacDonald was Rudyard Kipling’s mother, while her sister Louisa was the mother of Stanley Baldwin. Their two other sister, Georgiana and Agnes, married the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne–Jones, and the painter and President of the Royal Academy, Sir Edward Poynter, respectively.

Flanders also goes as far as to mention that, shortly after their marriage, Elsie and George were posted to Madrid and France. When they came to England they travelled in great style, with a chauffeur, a maid for Elsie, and a Spanish valet in elaborate livery for George. It has been suggested that the Bambridges’ footmen were suspiciously good-looking. It was generally accepted by friends that this was a marriage blanc that suited both parties: Bambridge was kept in the style to which he aspired; Elsie got away from home.

The one thing, however, that George Bambridge could claim was the ‘Bambridge Legacy’ – a trust fund Louis Floersheim had set up for him that amounted to £27,500. This was stated in detail in Louis‘ will from several years earlier, but it appears that George only became aware of this when he mentioned his upcoming nuptials to his Aunt Julia. The Kiplings duly met with Julia Floersheim and also agreed to add to the settlement so that the newly-married couple could live from the combined interest. However, Rudyard also seems to have played a pivotal role in buying properties for Elsie and her husband, and it is clear that Bambridge benefitted greatly from having such a wealthy father-in-law.

Interestingly, I came across a coded reference to Julia Floersheim in one of the letters Rudyard sent George (part of the Kipling correspondence at the University of Sussex) in which he writes to his son-in-law from The Grand Pump Room Hotel in Bath on January 6th, 1932. The first two paragraphs of his letter are as follows:

Dear Old Man –

Yours of the 3rd (reference to a letter written by Bambridge 3 days earlier) – one can only fall back on the old useless proverb – “no good crying over spilt milk” etc.: but it’s damnably annoying and what makes us both dance with rage is to think of where and how all those monies over the years of her widow-hood were squandered and robbed, by her own attendants – and all for nothing.

The other possibility (of equal share in the income) I never thought likely. The second chance we did think might be pulled off. But, every way, please take our sincere understanding. Your Aunt was right. Money is the cause of all the troubles in the world.

Julia Floersheim had in fact died the previous month, leaving an estate of several thousand pounds – a fraction of what Louis had possessed fourteen years earlier. This sum (once expenses were deducted) was to be divided between her three children and nephew. In contrast to the large legacy Bambridge had received from his uncle, his inheritance from his aunt would amount to very little in relation to the lavish lifestyle he craved. Moreover, Julia Floersheim’s will itself had not been changed for over a decade and mentioned that Bambridge should have all the furniture from his room in her house at 11, Hyde Park, in addition to the wardrobe in the library. I am sure that Bambridge (who would go on to furnish his homes with Elsie in fine style) would have been pleased about that!

The Kipling-Bambridge wedding took place on October 22nd, 1924, at St Margaret’s Chapel, Westminster (the small chapel next to the Abbey). As to be expected, the great and the good were there, including Mr and Mrs Stanley Skelton (brother of Maude Beatrice – more about him next month), although no Floersheims appeared to be present. The reception was held at the home of Stanley Baldwin at 93, Eaton Sq. and The Times devotes several paragraphs to describing the event, in particular Elsie’s wedding dress and ‘going away’ outfit (the newly-weds left for Brussels that same day, where Bambridge was to take up an appointment).

Elsie Kipling and George Bambridge on their wedding day

Elsie Kipling and George Bambridge on their wedding day

According to the biographer Andrew Lycett, over the next few years the Kiplings lavished a great deal of money on the Bambridges – who they admonished for living beyond their means – paying out for cruises, cars and houses. The Bambridges’ lack of income was exacerbated when George gave up working for the Foreign Office in 1932, and Kipling agreed to pay the rent on their new home – Burgh House in Hampstead, where they lived until 1937, with their life very much focussed on entertaining.

After this, they then moved permanently to Wimpole Hall, a large and very grand Georgian House outside Cambridge, where they had once briefly lived earlier in the decade. They eventually bought the house with the inheritance they received after Rudyard and Carrie Kipling’s deaths in 1936 and 1939 respectively (when Elsie became the sole owner of her father’s works). Lycett points out that George had known the owners – the Agar-Robartes family – while a schoolboy at Eton, and had previously attended shooting parties on the estate, so perhaps from a young age had been infatuated by the grandeur of the place.

The National Trust website for Wimpole Hall states that: Captain and Mrs George Bambridge first rented Wimpole in 1937 and had bought it by 1942. The house was largely empty of contents, they set out buying pictures and furniture to fill the house. During the war the household moved into the basements. The house itself was not requisitioned by the War Office due to lack of mains electricity and primitive drainage and water supply. Captain Bambridge died in 1943 as a result of chill caught whilst out shooting. Elsie Bambridge was the only surviving child of Rudyard Kipling. She was able to use the substantial royalties from his books to refurbish the house. Mrs Bambridge bequeathed the house to the National Trust on her death aged 80 in 1976.

Wimpole Hall, Royston, Cambridgeshire

Wimpole Hall, Royston, Cambridgeshire

At Wimpole, the childless Bambridges devoted all their time and energy to managing the estate – with George calling himself simply ‘landowner’ on the 1939 Register. The year before he had placed an advert in The Times looking for a footman: Tall Second Footman of four required June 1st: height over 6 ft.: personal reference: age over 21 essential: thoroughly experienced: country only. Whether it was true that George only picked the best-looking footmen or not, one thing about their lifestyle was certainly not in dispute: the war would irrevocably change their way of life as it did for estate owners up and down the country.

Andrew Lycett points out that when Elsie Bambridge died in 1976, she ordered the destruction of all her diaries, alongside those of her husband and her mother, leading many scholars to wonder if there was a family secret she wished to conceal – perhaps in order to preserve her father’s reputation. Could this have been the reason why Elsie prevented publication of the first biography of Rudyard Kipling, leading to bitter recriminations with the author, Lord Birkenhead (a connection initially made through her late husband)?

The idea of the dark family secret which needs to be kept hidden from outsiders is certainly a potent one that is a recurrent theme in many different types of family histories – from biographies, to memoirs to fictionalised lives. And perhaps this is the reason why family historians (myself included) are often searching for such a story in their own genealogy.

The Incidental Genealogist, September 2017